Tokyo Metro (2018)

Committing To A Long Commute

Just a quick note to warn, this is an extensive review. After reviewing this title, I found myself with so very much to say. Hopefully on this occasion, the detail contained herein will better enable you to determine if this game is for you. I’ll work to be more concise in the future. Probably. Now, let’s pick up our briefcases and start our journey…

Japanese culture has had a massive impact on Western society, be it through their food, comics or cinema. Despite humility being a strongly valued trait amongst the people of Japan, the rich heritage and curious customs of this island nation have nonetheless reached far beyond its shores. However, in the board game world, this rich vein of inspiration has strangely been left untapped in many of its aspects. Publishers have drained the militaristic elements of feudal Japanese history dry, angry Samurai being plastered over many a game box, whilst the subtle vagaries of the more peaceful modern Japanese world have been largely ignored.

Jordan Draper aims to correct this oversight, using one of modern Japan’s most iconic features as the setting of his recent design effort. Tokyo Metro is the latest game from the one-man studio, Dark Flight Games, having previously caught my attention with Import|Export, a design cut from the cloth of the genre-defining, multi-use card game, Glory to Rome. More recently, Jordan has been working on a reprint of the classic Turin Market and a series of original designs set in modern Japan, his ‘Tokyo’ series of games.

An economic game, where the players act as investors, speculators, station builders and even bicyclists (I kid ye not), the primary objective in Tokyo Metro is to individually eek as much value from the in-place underground rail network as is humanly possible, via the means of several vehicles.

[Figurative vehicles, obviously – this game only features trains and bikes, and everyone knows the latter doesn’t really count for the purposes of adult conversation]

To this end, once the game’s five to seven rounds (scaling by player count) have concluded, the player with the most money wins. In life, as in art.

A Lotus by Any Other Name

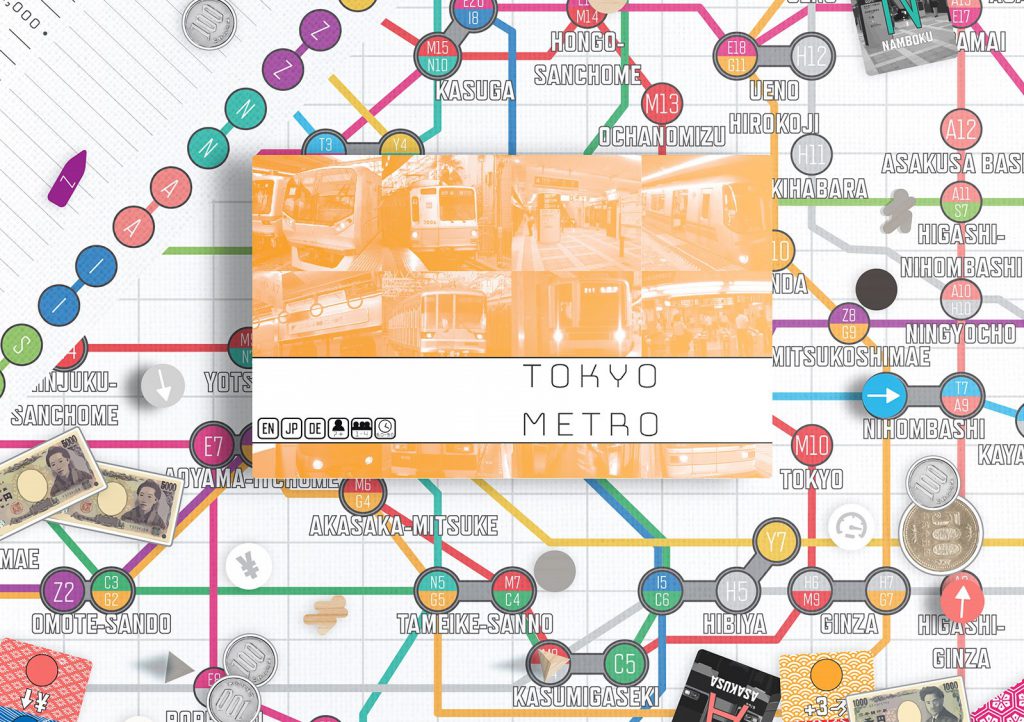

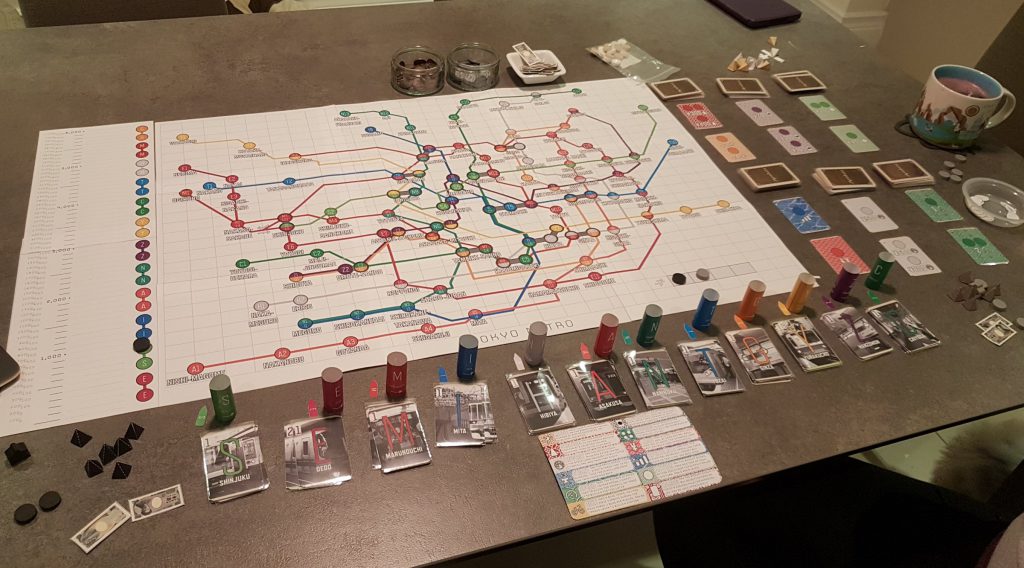

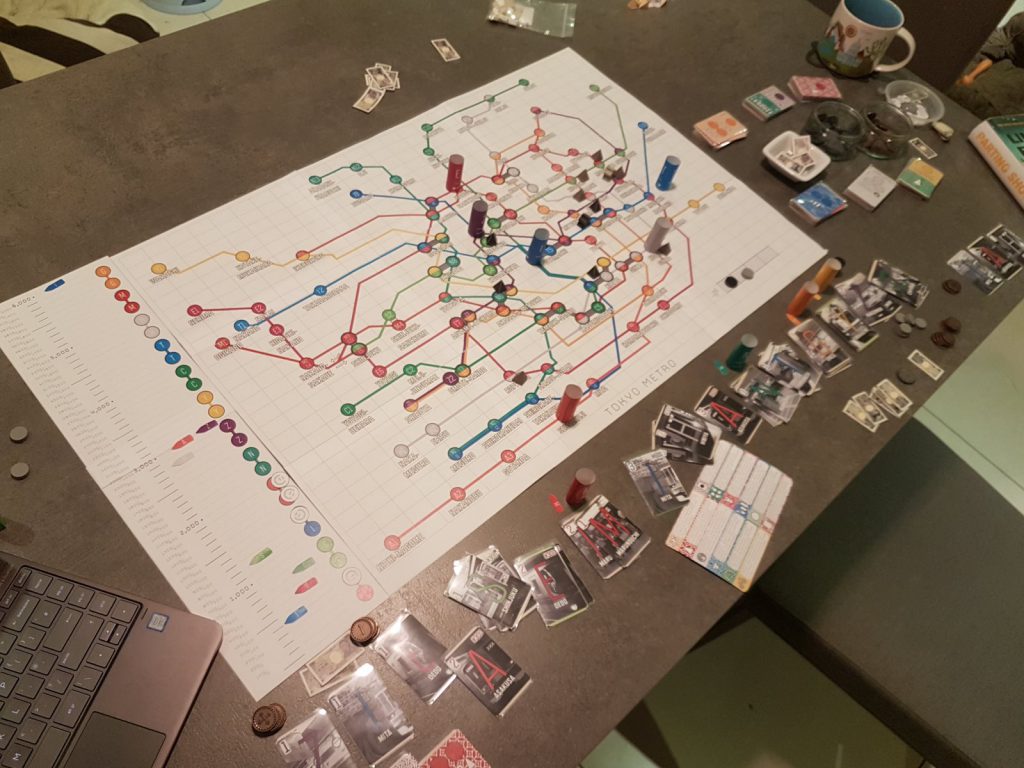

Much like alighting the train at the Shinjuku district, the first thing about the Tokyo Metro experience which is going to hit you is the striking visuals. Draper’s keen eye for clean graphics is apparent here, the central board being an expanse of clean white, broken up with subtle grid lines and sharp location markers.

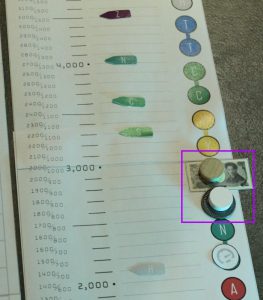

The company value tracker is similarly restrained, looking like a marriage between a steel ruler and a tide depth indicator, yet being able to convey a wealth of information about the game’s twelve train companies at a glance.

NEWSFLASH: Speculation ruins Z-line

The cards which provide the playing space for the worker placement aspect of this title are a further homage to the culture which has inspired this title, featuring Japanese inspired repeating patterns [Edit: Kimono prints, so I’m told] and a restrained colour palette which complements the hues used on the central map.

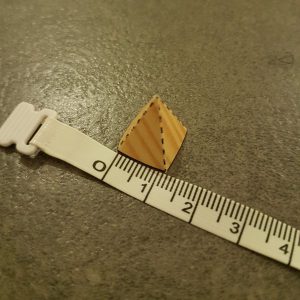

The cylindrical markers for train position and station location pyramids are an exercise in minimalism, feeling like something lifted directly from the parchment of an isometric schematic. By contrast, the currency used in the game has a more skeuomorphic design, being replica Nipponese monetary instruments made miniature. Read: diddy coins and notes. An aesthetically pleasing & clearly intentional juxtaposition.

(My outdated, cackhanded PnP components)

So far, so slick. I’d challenge anyone giving this a cursory inspection not to be at least intrigued, if not totally drawn in. However, visuals are really only worthy of note if the game’s mechanisms are up to snuff. Functional design trumps ornamental flourish when it comes to games, so just how does it play?

Gameplay: Mechanical Precision or Train Collision?

Tokyo Metro is one part spatial game, one part economic game, one part holdings game, two parts worker placement with a significant smidgen of ‘fun-ministration’ added to boot. Unlike many hybrids, the couplings between this game’s myriad elements feel seamlessly integrated, nothing feeling absolutely ‘tacked on’.

Following a closed bid auction for priority, players will begin each round with a free move, enabling them to walk two spaces on a grid overlaid map-homage of the Tokyo Underground railway system. Although the players speed on foot is quite limited, movement during the games early stages is quite critical, the players’ position dictating their options during the core work placement phase of each turn.

Following this short, somewhat stuttered dance (no diagonal movement allowed folks), the players will take turns selecting actions on the worker placement tableau in priority order.

Yes, I said worker placement ‘tableau’. Like Harbour and Mint works before it, Tokyo Metro uses a structured arrangement of cards as the playing area upon which the participants will place their action discs. There are six decks of cards, each consisting of families of actions and seeded in such a way that cards useful for the early game will come out, well, early. I’ll leave you to guess when the late game cards are engineered to come out. This is done by each deck being broken up into ‘eras’, the order of the cards within an era being entirely random. A number of cards from each deck equal to the number of participants involved are exposed in their own rows to set up the game. At the end of the turn, the stalest card of each pile is discarded and a new card is introduced to the top of each row from its associated draw deck, much like a series of parallel conveyor belts at a tuna cannery. The game ends at the end of the round when the tuna, sorry, cards run out.

This ever-shifting menu of actions is one of Tokyo Metro’s strongest elements, it being seeded in a way that ensures a consistently satisfying experience, yet randomised enough that each play should be tangibly different from the last. The timing with which cards become available for use or expire will need to be actively read by the players, certain strategies being more or less viable depending on how long given cards are a feature of the playing space. This is no mere curio, the card waterfall mechanism significantly enhancing Tokyo Metro’s replayability and depth, whilst incurring a pretty minimal setup and teardown overhead and a negligible complexity uplift.

At the start of proceedings, each executive will be assigned three action discs (referred to as ‘workers’ hereafter) and 2000 Yen start-up capital. Clearly, your management team is small and your financiers stingy/shrewd (delete as appropriate) as neither resource will go very far, if deployed unwisely.

When a worker is placed, in the majority of the twelve types of action spot, the activity is immediately resolved. Action discs are blocking, one exception aside, with no ‘bumping’ mechanism to take the brutal edge off. This blocking aspect is made all the more visceral due to the limited lifespan of each of the cards which compose the board.

You can use your transient wealth to purchase train stations, invest in train companies or speculate against your opposition’s holdings. In my view, these actions form the core of the game experience nor is their function immediately apparent, therefore demand that I expound upon them quite extensively to give you, fair reader, a reflection of the game’s best qualities. Read on, read on…

Going Deeper, Underground

- Build a station

Pay the cost listed on the card per intersection (round bit) on the station to buy the franchise for the station to which you are geographically adjacent. Stations are blocking, each franchise being exclusive to a single player.

Active stations will be your primary source of wealth, be it improving the value of the train companies you own (when one of your trains pass through) or increasing your liquid wealth via taxing other peoples’/unowned train companies to use your station, increasing your in-game options whilst giving their companies a modest bump in earnings.

Placing stations ‘well’ will be a key difference between a high and low performing executive. Investing in companies which traverse through your station should always be considered, however having a few third party trains run through your stations is key to keeping you sufficiently solvent to avail of tactical opportunities in a timely fashion. Speaking of which…

- Invest in a Train line

Paying the cost listed on the action spot, plus the tax stated on the share (latter shares costing more than earlier ones, simulating an increase in market value), buy the lowest numbered share still available of the three starting shares in a train line of your choice. The founders share trumps the second share which in turn trumps the third share, in terms of breaking ties.

The train of the company is placed upon the board, moving a minimum of five spots every turn for the rest of the game, bouncing off of the end of the line, to quote a friend, “like a train”.

Owning train lines is the player’s main means of being awarded end-game pay-outs, the majority share-holder being awarded two thirds of the company’s earnings at game end with the secondary share-holder receiving a meagre one third. In the event of a three-way split, the earnings are divided in a ratio of 50:33:17, roughly speaking. I haven’t given it that much thought, but that third share seems to represent rather atrocious value, unless you’re planning to wrest the presidency from someone, and who would do that? Let’s just leave each other’s companies alone, yeah? Yeah? Please? Oh.

- Speculate against a train line

That liquidity you just drained by building stations and investing in train-lines could have, of course, been used other ways. Perhaps you would have rather taken this action spot, to stake it against an opponent’s company? Place a worker here to release one of your two speculation discs which must immediately be assigned against a train line in which you have no ownership, along with some cold, hard cash, to be locked out until the end of the game, along with some ill-gotten earnings. There are some rules in place surrounding minimum stake, maximum pay-outs and some defensive strategies available in order to stop the whole game becoming a Dick Turpin affair, however it is critical to note that there is no maximum bet and returns against the speculation directly detract from the train company’s value before end-game dividends are awarded. No shares left? No problem. If you can’t get value from a company the old fashioned way, ‘old man speculation’ is your fella.

There’s a smattering of other action types available to the players throughout the course of the game, all of which add nuance to the proceedings…

…okay. There are significantly more than a smattering, as there are nine other types of actions BUT many are standard worker placement fare. Be it the acquisition of extra workers and the associated extreme challenge of funding their activities, or the pitching of a turn to discount a future action, but with the risk that your planned action gets gobbled up by one of your greedy, greedy friends, the other offerings feel quite refined if not absolutely original in and of themselves.

Worthy of mention are the Martin Wallace spots (Take Loan and Repay Loan) where you can get money (1000 Yen) to deploy as you will, but will be somewhat punished if you don’t repay the debt (50% interest). Unlike other games featuring loans however, it’s not a foregone conclusion that the most profitable route is the repaying of them, which I think makes for an interesting take on the mechanism.

Also warranting detail, the ‘card’ spot is very interesting, enabling the purchase of the top card from any of the discard piles for private use. This is normally quite costly, but situationally can represent fantastic value, be it financially or strategically. It’s a touch that really complements the rolling action tableau phenomenally.

There’s a variety of other scams and optimisations on the menu, including but not limited to bonus movement, tokens to drive up the speed of trains or your player pawn, and grossly discounted station builds. Needless to say, there’s a lot going on in combination, yet no spot in isolation in unfathomable, which makes Tokyo Metro a joy to teach, given the depth on offer. If you want more detail, I’ll humbly refer you to the publicly available manual. It might not give you strategy tips, but it’ll probably be less contrary than my good self. And less verbose.

Trains, Trains and Something Else

Following the worker placement phase, everyone either having deployed their workers or having passed, the ‘Train Phase’ commences. It’s more fun than it sounds, possibly. I mean, for the purposes of debate let us assume our definitions of fun align, but be warned that I’ve been known to be entertained by Microsoft Excel…

During the Train Phase, each train on the board is moved, in a defined order, five stops along its line. Should a train reach the end of its line, it will be turned around, the orientation arrow changed so that the direction of travel is clear, and its journey continued.

If a train passes through the station of a player who owns stock in the company, then the train company will increase in value by 500 Yen, thanks to all of those ticket sales. Hooray (!) for your end-game pay-out.

If a train passes through the station of a non-shareholder, then the train company will receive 200 Yen of the ticket sales as company value and the station owner will receive 200 Yen to spend as they please during the game. The other 100 Yen? Wasted on the lawyers, probably.

Should a train pass your player pawn, you can hop onto it, albeit for a nominal cost, enabling you to build stations on new parts of the board.

[Editor: Even a nominal cost is significant if you’re stony broke #JustSaying]

Should you hop off at the right intersections, it’s entirely plausible to ride multiple trains on a single turn. As satisfying as a well-timed commute, where the Starbucks barista gets your name right.

This process is repeated for each of the active train companies, pay-outs being awarded and company value tracked. Once all the trains have been operated, the game cycles into its next turn, the card conveyer belt being incremented by a notch and priority once again being up for auction.

I’d be remiss right now if I did not expand, extensively, on the character of the Train Phase. Let me be entirely clear that the amount of enjoyment you derive from this type of administration will in significant part inform your experience of Tokyo Metro. I estimate that in an average game you’ll be calculating the pay-out for 30 train runs. The Train Phase breaks the rhythm of the Turn Order, Movement and Action phases which use more classic mechanical tropes. This may be for better or for worse, depending on your appetite for moving little tubes along train line abstractions.

To my mind, there’s something slightly meditative about moving the tubes along their routes, assigning pay-outs to players and companies like some sort of railway croupier, the low-level maths being relaxing. However, others I have played Tokyo Metro with have said that it reminded them of the burdensome administration required in Dominant Species on some sort of sub-atomic level. I can’t say I see that, as Dominant Species ‘problem’ is that nearly every action can have a butterfly effect on table state, requiring the players keep an eye on it during each every action resolution. With this title, the calculations are simpler and the game state less violently volatile, but I cede the point that the largely deterministic phase is a cognitive shift from the ‘play’ phases where decisions are made.

In my experience, it takes three or four turns for new players to comprehend how to drive the Train Phase themselves. It is therefore also possible to conclude that players won’t be playing their best game from the offset, the ability to forecast company value by reading the table state being linked to at least a basic understanding of the Train Phase.

[A view which repeats itself in my analysis, is a belief that nothing worth doing comes easily and games which are possible to unpack mechanically after one turn probably don’t pack infinite depths of replayability]

That’s not to say that it’s difficult. There are only two rules for pay-outs which are pretty darn basic in nature. I’d say, pitched correctly by the instructor, leading the Train Phase is intuitive but not absolutely rudimentary. However, you were told going in that this was an economic game, so there is a basement to how simple things can get before we’ve extracted the depth out of the genre to paddling pool levels of triviality.

A Drawn Out, Analytical, Conclusion

I’ll preface my conclusions with some disclaimers before we get into the pampas grass of it:

- I don’t have a long history with train games

- I like economy games

- It took about 5 hours to make the PnP kit, so it’s entirely possible my investment in putting this game together could have imparted bias

Without a shadow of a doubt, Tokyo Metro is the most interesting game I played in December 2017, in a December where I played a disproportionately high number of new games. There’s decent depth contained herein without outrageous amounts of complexity to enable it. It’s not the last word on any single given mechanism, but the blend of elements is unique and they are exceedingly well coupled in their integration to each other, as stated at the outset.

Each of my run-throughs, in their own way, have been a bit of a joy, the 2-2.5 hour runtime never feeling like a burden, my engagement ensured entirely throughout.

The interactivity in this title is really up there with some of the strongest titles I’ve played this year. I care where you place your stations. I care which train companies you own or have expressed interest in, be it explicitly or implicitly. I certainly care about your options to enhance or attack my company’s value, be it via mutualistic station placement or cynical, anger-inducing speculation. I certainly care when you block one of the key spots on the worker placement board that, due to the cascading cards, will not be available to me next turn, unless I’m willing to pay through the nose to dig it out of the bin. What you do matters. What I do (hopefully) matters.

[Well, when it comes to this game anyway – maybe not in a nihilistic sense #TeamNietzsche ]

It certainly passes the ‘does it make me feel’ test, a measure I coined when playing Kraftwagen for the first time two years ago, realising that it was one of very few board-games that created genuine endorphin highs and contextually abysmal lows. Although very few titles out there compare to this most elegant of emotion amplifiers, Tokyo Metro certainly, at points, evoked a very similar depth of feeling. Feelings I saw mirrored in my opponents across the table on numerous occasions throughout testing through the expression on their faces and the tone of surrender in their voices when they’d realised… what… I… had… done.

A point of query that I can imagine coming up is how does it compare to an 18XX title? In two words: it doesn’t.

[whispers… and that’s okay]

I can’t hand on heart call it a ‘Train Game’ as the stocks system is a bit too basic and you aren’t laying any tracks. But does that matter? I’d argue it’s an interesting title in its own right, even if it doesn’t fit a convenient archetype. Tokyo Metro seems to trigger many of the same synapses for me, using distilled versions of ‘Train Game’ mechanisms, whilst bringing in some classic Euro-game mechanisms to the party. Much in the same brain-melting way that For-Ex appeals to the players of train games, despite featuring absolutely no rolling stock, Tokyo Metro provides ample interactive decision space, alive with possibilities and an opaqueness the fanciers of the finest of hostile titles have taught themselves to appreciate.

Every playgroup I have put it in front of have responded very positively, be it classic Euro Gamers through to hard-core 18XX enthusiasts. I’m yet to stick it in front of a D&D group, but I remain ever hopeful that they won’t scatter in fear when I enter a room. I really should stop wearing that rubber Orc mask. Or start wearing trousers. One or the other.

Most strikingly, every instance of Tokyo Metro has played out differently, there being structurally higher value lines on the map by design, but the players’ actions dictating which companies thrived and which ones died. Replayability largely defined by player behaviour is a sublime treat indeed, the experiences being as myriad as the personalities and approaches of the participants at the table.

Most critique shared with me has largely been related to my lacklustre Print and Play implementation or being something Jordan Draper is already looking at as part of development.

But that’s not to say it’s without its flaws.

Although most of the abstractions in this game feel solidly linked to the theme, therefore easily explained, a couple of elements stood out as ‘awkward’, specifically trading in tokens for stations and speculation.

Speculation is a game device mechanically necessary to attack your opponent’s company value, should the option of share ownership be removed from you. You need something to stamp on the neck of a rocket-ship route in which you have no interest. In the absence of such a mechanism, it would be possible for a someone who engineered a good route and share defence to be a fait accompli winner, the remainder of the game being a mere procession or funeral march, if you will.

However, try as I may, I cannot succinctly explain to my more literal thinking friends why the pay-outs from speculation against a company are awarded from said company’s coffers, yet the company concerned at no stage really gets to handle the money. I’ve had to ask my friends just to ‘go with it’ as a mathematical trick, by game-end everyone appreciating what it brings to the proceedings.

The weirdness of speculation fades into nothing when compared to the prospect of trading in a bike token for a train station, being one of the aforementioned scams referenced about 300 paragraphs (or so, roughly) back. This was initially so jarring that I asked the designer what his thoughts behind the idea were. His response was quite insightful, Jordan responding “I wanted to remind people that it’s just a game” (or words to that effect).

[It did remind me that some of my favourite games are NOT hard simulations. I don’t feel like I’m actually building cars in Kraftwagen or making wine in Vinhos, but I’d never turn down a game of either of those, quelle surprise]

The ‘tokens for stations’ abstraction undeniably works as a mechanism here, allowing those who are willing to play ‘chicken’ long enough to extricate outrageous value from the board, albeit at a risk of losing key opportunities. Notably, my audiences had less of an issue internalizing the enigma than I did. Perhaps it’s ludicrous enough that it demands suspension of disbelief from the audience whereas the ‘nearer the mark’ speculation activity is close enough to real life that the brain keeps trying to make sense of it.

That all being said, after one play, the thematic foibles of these two mechanisms are ignored in the light of the decisions they enable.

If I was being very harsh, I’d say that the scale of cyclopean, uniformly shaped train markers and the miniscule stations are somewhat off, making a congested centre of the map quite hard to work with. I’ve been advised that the component scaling is in large part a product of the PnP file and already being addressed by the designer to make the map more easily scanned at a distance.

I have also had some feedback that the colours selected for the lines are very tough for red-green colour blind players to work with. Although every element is technically double-encoded, the lines having letters and numbers on every stop, there’s a possibility the map could be made easier to parse at a glance by adding textures to the problematic lines.

In his defence, Jordan is constrained here by the colours on the Tokyo Metro map to which he is being inspired. Furthermore, it’s a tough ask finding twelve colour blind safe colours to work with. To his credit, I’m seeing him tweak the colour palette on every revision of the PnP file and, to my understanding, he is graciously accepting feedback on the visual design.

End Of The Line

In closing, I’d like to reiterate: this game is exciting, but not in the conventional way of ‘contains glossy components’ or ‘hyped from a super marketing drive’. It excites me due to mechanical rigour, providing a platform for an exceptionally interactive experience. Furthermore, I can say, without reservation that it is not like anything else I’ve seen before, be it in the blend of mechanisms contained within or in terms of the aesthetic approach taken. You have to applaud that, to my mind. Viva la difference.

Whether it will stand the test of time is hard to say at this point, but given the uniqueness of my test runs to date, I’m very hopeful. Three games in, I felt I had developed an idea how to ‘not play incompetently’. I’m still not sure how to respond to every move or even ‘see’ every play being made with even more plays under my belt. It’s certainly dense enough that I’m not worried about wearing it out anytime soon, despite not being as gloriously opaque as For-Ex. Being philosophical, perhaps limiting a titles opaqueness is ultimately a good thing, even amongst the hard-core brigade? The accessibility is decent enough that I can forecast my being able to cultivate several sizeable playgroups for Tokyo Metro, something I just cannot conceive for the currency exchange game to which I am comparing it.

Tokyo Metro is now currently live on Kickstarter, as part of Draper’s Tokyo Games campaign. Of particular interest to me is the Tokyo Metro compatible Tokyo Jidohanbaiki expansion, which adds the option of deploying soft drink vending machines to the expanding station network, releasing liquid capital into a financially constrained system.

Although I can’t do this expansion justice in the confines of this review, I’m curious enough that I’ve put together my own PnP kit in order to try it out, with an intention of authoring a follow-up micro-review, which I’ll link here in due course. If you’ve done a PnP before, you know what a pain in the caboose it is, so can probably gauge the promise I believe the expansion holds.

The rules are available for the expansion in the currently published Tokyo Metro rulebook, should you wish to give it a pass yourself. If you want a parts list, feel free to pop me an email.